Articles

Exploring History's Greatest Adventures throughout time!

Letter Writing During The American Civil War

By Peter Serko, author of Hattie’s War

When was the last time you sent someone a letter?

Maybe never. Letter writing has become something of a lost art. I rarely write letters these days. Email, social media, texting and video calling have replaced letter writing as a way of staying in touch with others.

During the Civil War era, letter writing was a significant activity. It was the only way of staying in touch. People used quilled pens or pencils to write letters. Good penmanship was prized and even a casual letter was embellished with fancy flourishes.

For many soldiers, this was their first time away from home and family. The army soon recognized that mail was essential to maintaining troop morale and established postal details that followed the troops. A postal wagon or tent served as a temporary post office for soldiers in the field. Soldiers often had lots of downtime, spending weeks and even months in camp, particularly early in the war. Letter writing was one way to pass the time.

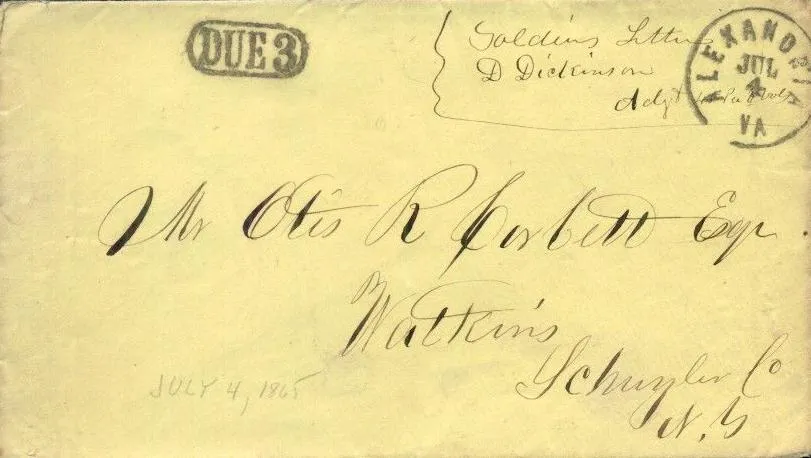

Even then, letters required a postage stamp. It cost three cents to mail a letter during the war. However, it soon became apparent that many soldiers couldn’t afford stamps or didn’t have access to stamps. Legislation in 1862 made it possible for soldiers to mail letters simply by writing “Soldier’s Letter” in the upper right corner in lieu of a stamp. Postage was then collected from the person receiving the letter.

So many letters were written during the war that many still survive today, offering scholars, students, and Civil War enthusiasts a glimpse into a soldier’s life during that time. Since letter writing is important to the story of Hattie’s War, I read dozens of soldiers’ letters readily available online.

A letter-based peek into my ancestry

Thanks to a distant cousin* I learned about Hannibal Howell, who was Hattie’s father. She never knew him since she was born five months after he left home to fight in the Civil War. Hattie is my great-great-grandmother and Hannibal is my great-great-great grandfather.

Hannibal volunteered to join the Union Army with two of his brothers in September 1861. Only one brother, Byron, survived the war. After the war, Byron became a contractor during Reconstruction, the federal government’s effort to rebuild the South. The Byron character in the book is built around a number of the real Byron’s letters written after the war to his younger brother Milo.

It got me thinking: Wouldn’t it be something if I had letters written by Hannibal? I’d put the chances of finding any letter at practically zero. He died 160 years ago. I barely knew anything about his life other than details of his military service and who in the family was left behind. His body was never identified or recovered. Most likely, he is buried in one of the “unknown” graves section at Gettysburg Military Cemetery.

Then… well into the writing of Hattie’s War, I had a chance email exchange with a distant relative. I was looking for information about Hattie and her family. I mentioned, offhand, I’d love to find letters written by anyone in the family from that time. Several weeks later, she wrote back, saying she was in touch with a woman who had letters written by Hannibal Howell. Eureka! It turns out the woman with the letters was my cousin Lois, whom I hadn’t seen in more than fifty years. I got Lois’s address from my mother and wrote her a letter. (I typed it — so much for good penmanship.)

Long story short, she sent me copies of 12 letters Hannibal wrote between 1858 and 1862. Many of the letters included the envelopes. His letters often started with the greeting “Dear Brother.” I wondered which brother he was addressing. Hannibal came from a family of fourteen children. It was not until I looked at the envelopes that I realized the letters were written to his brother-in-law, Mortier Lafayette Wickham.

Hannibal had an interesting closing to many letters: “No more at present.”

What a thrill to be able to read his words and gain some insight into who he was. I immediately incorporated one of his letters into the story.

Dear Brother,

Your [letter] of the 24the mailed [on] the 26th came to my hand last night. I haste to answer it but I shall have to be brief as the mail leaves soon. I will say that my general health is good although I have a cough from the effects of cold caught some time ago. We have had another move since I last wrote to you from Meridian Hill to Fort Slocum four miles distant . . . [S]ix miles from Washington in a northwesterly direction. [T]here is two companines to guard this fort it covers 1/2 acre. [T]he rest of our regiment is placed in four different forts from one to three miles apart . . . [T]he headquarters Fort Toten has three compines and is three quarters of mile distant. [T]here is ten twenty four pounders in our fort. [O]ur Colnoel has had further dificulty . . . [he] has been arrested [and]examined before a board[.] [He was] found guilty of charges conseqently we are expecting a new Colonel. In regard to moveing[,] I do not approve of it though I shal abide by the decision of my wife[.] [T]he move will be attended with trouble and expense . . . [M]y wife mentions moveing in with another family that would be bad[.] . . . [F]urther I expect that if my life is spared that I . . . shal return in a few months of June [or] July at the fartherest. We have had some glorious victories lately and there is events transpireing almost every day that strenthens my faith . . .

I must cut short.

Hannibal

(Transcript of the original letter. Errors in the original)

This letter is dated March 9, 1862 (my birthday is March 9th), when Hannibal was stationed with his regiment, the NY 76th, at Fort Slocum in Washington, DC. The NY 76th spent about six months in Washington protecting the capital before moving to Fredricksburg, Virginia, and the beginning of their journey into the abyss of war.

Although Hannibal wrote about soon returning home, it was not to be. The war lingered much longer than the soldiers’ confidences allowed. Sixteen months later, Hannibal was dead, killed in the opening moments of The Battle of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863.

Recommended Reading

Hattie's War by Peter Serko

Hattie's War is the story of a young girl's quest to find herself and her place in the world in an era when women had few options. Plagued by debilitating depression, a "curse" that runs in her family, 14-yeaar old Hattie fears being sent to an insane asylum. Against all odds, she bucks convention, guided and supported by a most unlikely cast of characters. Her courage and determination finally pay off. Yet, in the end, she makes a surprising decision.

Set against the backdrop of the post-Civil War, Hattie's War draws on true first-hand accounts of those who fought in the War. Hattie, in real life, is the author's great-great-grandmother.

Activities and further research

Explore the Library of Congress here to find and read thousands of Civil War documents, including soldiers letters.

Learn what was happening when during the Civil War on this timeline.

Download from our Free Resource Library a Civil War letter writing activity to do with a friend or partner.

© 2023. Historic Books for Kids - All Rights Reserved

Reading Pennsylvania, USA